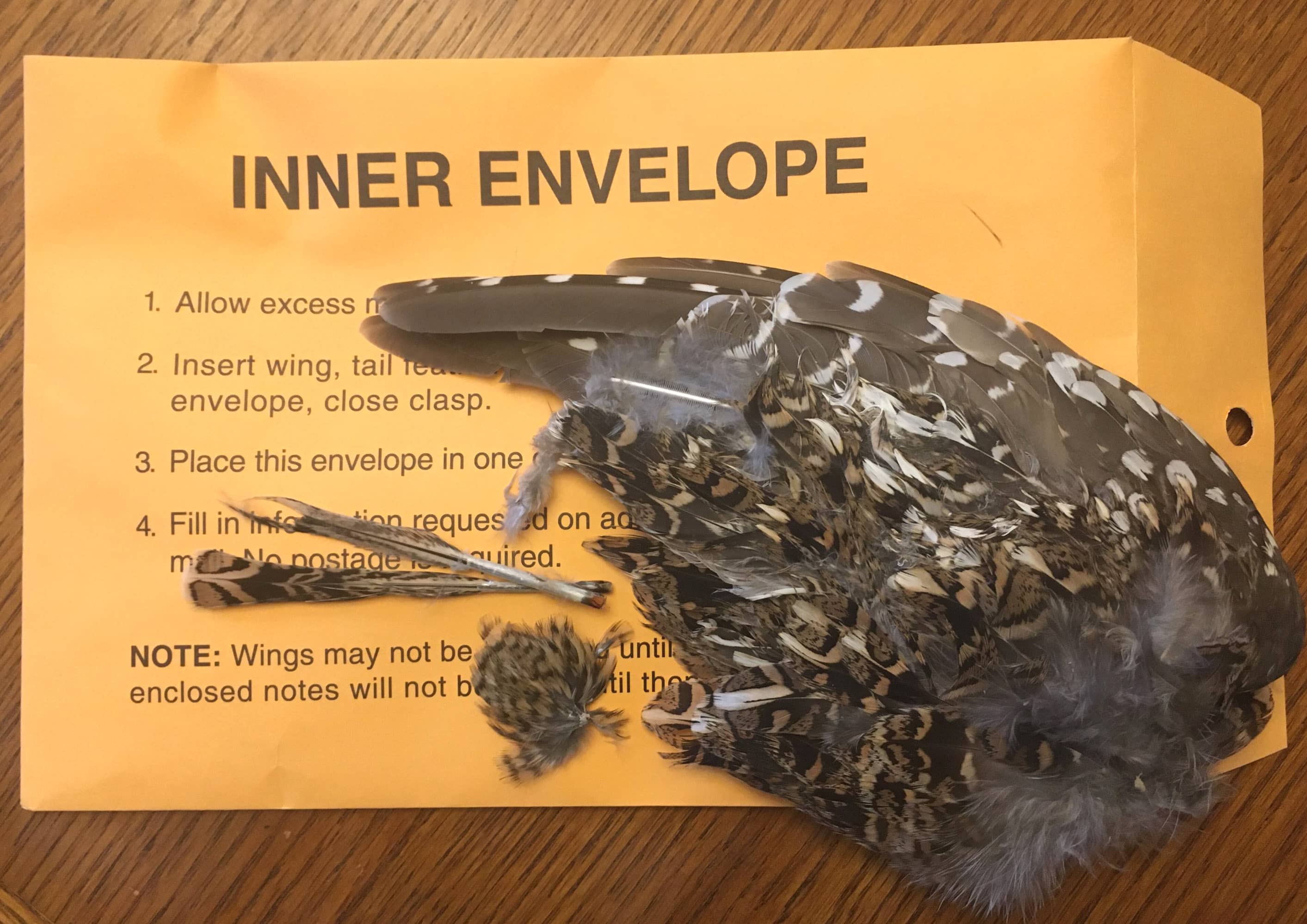

The wing, tailfeathers and head feathers of a harvested sharptailed grouse are put in an envelope and submitted to the NDG&F. In total, the agency handles thousands of wings each year from the state’s three major upland game species. Simonson Photo.

By Nick Simonson

While the upland bird hunting seasons have ended in North Dakota, the work for the staff of the state’s Game and Fish Department (NDG&F) is just getting underway in an effort to tally hunter hours in the field, their relative success and also the data from submitted samples to help gain the information needed through surveys and wings submitted by sportsmen.

Through those hunter surveys and sample envelopes, biologists and staff can determine sportsman effort, estimated total harvest of pheasants, grouse and partridge and insight into the makeup of those populations in the most recently completed year. According to NDG&F Upland Game Management Supervisor Jesse Kolar, both resources provide more than just the numbers, but insight into trends, habitat initiatives and management practices of the agency.

Survey Says

Each winter the NDG&F sends out surveys to select hunters throughout the state to determine their participation in and success from upland hunting endeavors for pheasants, sharptailed grouse and Hungarian partridge. From that, agents get a bootstrap sampling of how many birds of each species were taken in the previous fall and gauge hunter efforts in the field.

“We try to get a feedback on one, how satisfied people are with their seasons, but also on how many total pheasants, partridge, [and] grouse are being shot each season, that information helps not only with our legal mandate to report those things in order to have hunting seasons, but it also helps us to evaluate how the trends are correlating with what we’re seeing on our surveys and how hunters are experiencing numbers based on what our surveys are showing,” Kolar explains.

Winging It

At the outset of the fall upland hunting season, sportsmen can request wing envelopes through the NDG&F and its offices around the state to catalog samples of wings, legs and various feathers of upland species to help biologists determine the estimated makeup of pheasant, grouse and partridge populations in the areas they hunt. By receiving the wings, legs and certain head feathers, biologists can determine the age structure of pheasants on the landscape, and can also determine the same for grouse and partridge along with the gender makeup of the populations during the season. On the average the department receives 2,000 to 4,000 pheasant wing samples, around 1,000 from sharptailed grouse and a few hundred partridge submissions each year, though those numbers have been off since the drought of 2017.

“That’s an important sample we get and it has been a sample that we’ve been low on in the last few years, obviously with low numbers harvest has been lower, so we haven’t been getting as many wings sent in from hunters as we normally did,” Kolar states of those recent submission trends, “it doesn’t take too long to go through each envelope and once we get rolling…we can usually go through 50 to 100 every hour, but we don’t set up and do that every day, it’s usually free afternoons here and there and it takes us a few months,” he concludes.

Deep Dive

Beyond just knowing what’s out there season to season and confirming spring and summer survey results, the data obtained from hunter surveys and wing submissions help the NDG&F in conjunction with other data to determine possible habitat efforts in certain areas and assist with management of state lands for upland game birds. In places where numbers are off, private land initiative efforts can be ramped up to improve areas of habitat to help sustain and rebuild pheasant and grouse populations. In the instances of getting a better understanding of the science and biology of upland game management, the average age can help determine hatch times and practices relating to improving survival.

“Recently we did an evaluation of all the wings that we’ve had since the 1950s and we were looking at nearly 200,000 total pheasant wings and 70,000 total sharptail wings, a lot of wings that we’ve aged and sexed over the years,” Kolar related as part of a study to determine the prime hatching dates for sharptailed grouse, and it was discovered that about 30 percent of the young birds were vulnerable to haying practices into August, “that changed how we’re managing our wildlife management areas; we’ve now shifted our haying date from mid-July to early August, so things like that are impacted directly from these numbers,” he concluded.

From the basics of hunter efforts and harvest composition to deeper biological concerns and management improvements, the two-tiered set of winter tools at the department’s disposal go beyond days afield and the feathers on a wing. As a result of hunter participation in these efforts, the agency is better able to understand the intricate relation of habitat, birds, hunters and so much more on the prairie of North Dakota from season to season.