NDSU Extension

North Dakota producers depend on forage as their primary source of nutrients for livestock, whether it is rangeland, pasture or hay.

While producers carefully select species to be used as cover crops or part of a total mixed ration, many ranchers do not know the primary grass species their livestock is consuming, according to North Dakota State University Extension livestock specialists.

“Knowing the predominant grass species on their operation is important for ranchers because not all grass is created equally,” says Miranda Meehan, Extension livestock environmental stewardship specialist. “Different species have different growth patterns and nutritional content, which can influence livestock performance. In addition, grass composition is a good indicator of ecosystem health within rangelands.”

In the northern Great Plains, native grasslands consist of a mixture of cool- and warm-season grasses. Native cool-season grasses begin growing once the average temperature is 32 degrees or greater for five consecutive days (typically mid-March) and reach grazing readiness in mid to late May, whereas warm-season grasses start growing once the average temperature is 40 degrees or greater for five consecutive days (typically early April) and reach grazing readiness in mid to late June.

Pasture, on the other hand, typically consists of cool-season species that exhibit rapid growth in the spring, permitting grazing in late April to early May. This extends the grazing season by enabling ranchers to head to pasture earlier in the spring.

“Timing and intensity of grazing influences species composition within a pasture,” Meehan says “For example, grazing the same pasture every year in July will result in increased consumption of warm-season grasses and an increase in cool-season grasses. Rotating the season of use of pastures helps maintain the balance of warm- and cool-season grasses, whereas long-term overgrazing favors short-growing natives and Kentucky bluegrass, which are better adapted to heavy grazing pressure.”

Grazing before grass plants reach the appropriate stage of growth for grazing readiness causes a reduction in herbage production by as much as 60%, which can reduce the recommended stocking rate and/or animal performance. Grazing readiness for most domesticated pasture is at the three-leaf stage, whereas grazing readiness for most native range grasses is the 3 1/2-leaf stage.

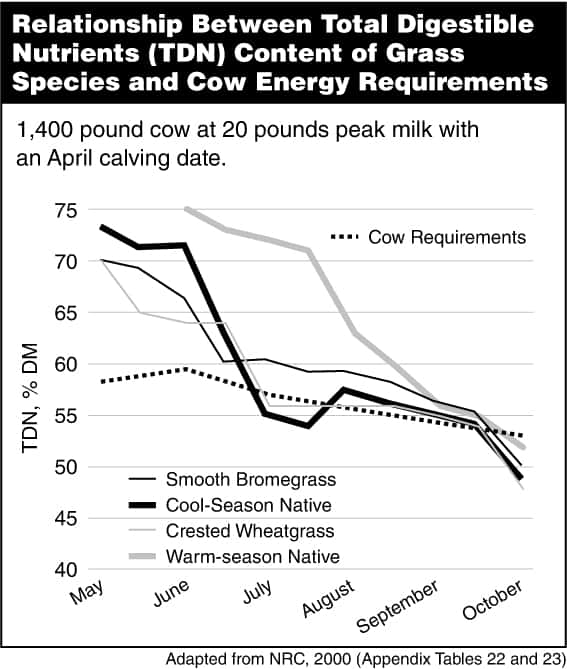

“The advantage of having grasslands consisting of cool- and warm-season species is that the nutritional plane is more even,” says Janna Block, Extension livestock systems specialist based at NDSU’s Hettinger Research Extension Center. “Thus, the grasslands are able to meet the nutritional needs of cow herds without supplementation for a larger portion of the grazing season.”

Meehan notes: “Unfortunately, many grasslands in the northern Great Plains are becoming cool-season dominant due to changes in composition. More specifically, this is due to the invasion of the cool-season introduced grasses Kentucky bluegrass and smooth brome.”

Typically, pasture turnout takes place in mid-May to early June, when grasses are growing actively. At this time, crude protein and total digestible nutrient (TDN) levels are high (greater than 15% and 60%, respectively).

By the end of the growing season, standing forage is low in crude protein, with cool-season species being about 5% and warm-season species being between 4% and 8%, depending on the species. Energy also will be low for these forages, with cool-season species falling below 50% TDN and warm-season species at about 52% TDN.

Understanding the relationship between forage quality and the nutrient requirements of livestock is important, Block says. Peak lactation occurs about 60 days after calving and represents the most nutritionally demanding period in the production cycle. While forages typically meet requirements for lactating cows during late May and early June, cows that are calving prior to the first part of April will reach peak milk production prior to that point.

“In addition, turning cows out on pasture too early will have negative impacts on forage health and production,” Block adds. “Alternative forage sources and/or supplements should be provided in early spring to meet increased requirements during lactation.”

Knowledge of your grasses can be used to make management decisions that improve forage composition, quality and production, the specialists say. This information can be used to guide grazing management.

“Enhanced knowledge of your grass species can improve pasture and herd health,” Meehan says. “Knowing your grasses enables you to make sure that the nutritional needs of your herd are being met, improving growth and reproduction. It also can be used to make management decisions that will improve species composition, which in turn can benefit livestock performance.”

For assistance in learning about and monitoring grasses in your native and tame pastures, contact your local NDSU Extension agent or Natural Resources Conservation Service office.